For many of us, our parents actually taught us to drive — from sitting in the car and learning how to adjust the mirrors, to puttering around in a parking lot or similar location trying to avoid obstacles and learning the ropes.

But as our parents and loved ones age, their ability to drive safely deteriorates, and suddenly we’re reversing roles. It can be a tough conversation to have.

For many older Americans, driving equals independence. Do they really pose a threat? The statistics tell a cautionary story, but every situation is unique. What are the telltale signs that you are too old to drive? And how do you tell an elderly person to stop driving, or that they can’t drive anymore?

I’m going to arm you with the information you need to have that talk.

Statistical Reasons Why Some of the Elderly Should Not Drive (Or Should Drive Less)

As you might expect, there are many studies and mountains of data surrounding the driving habits of our senior citizens. The key, as always, is to understand that every person is unique, and as such, each person should be measured by their own ability.

Generally speaking, though, the senior driving statistics send a fairly clear message.

There Are More Senior Drivers on the Road Than Ever Before

According to Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) data, there were more than 45 million licensed drivers aged 65 and older in 2018 — a 60% increase from the year 2000. Nearly 8,000 people in the baby boom generation turn 65 every day, and by 2030, there will be more than 70 million people age 65 or over, and 85% to 90% will be licensed to drive!

Seniors Drive Fewer Miles, But Have Higher Accident and Injury Rates

Based on travel data from the FHWA obtained by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS), seniors drive fewer miles than average, but those miles are increasing. On average, drivers aged 70 and older drove 43% fewer miles than those aged 35 to 54. But, according to data from 1996-2016, the mileage driven by seniors increased 65%.

So, senior drivers still drive less than most, but they’re driving farther each year.

Older drivers tend to have lower numbers of crashes, but that correlates to driving fewer miles. If you observe the number of crashes and injuries per mile traveled, the numbers tell a different story.

Elderly driving safety statistically begins to decline at about age 70. From that point on, the risk per mile traveled increases. It doesn’t help that, according to research, older drivers (like many other low-mileage drivers) tend to do much of their driving in cities, where accidents are more common than on highways — which are often divided, multi-lane roads.

Aging Drivers Are at Increased Risk of Injury in an Accident

The older we get, the more fragile our bodies become. Fragility begins in middle age and increases as we get older. The rate of fatalities among older drivers involved in wrecks begins to sharply increase between ages 65 and 69. In terms of fatalities, older drivers are typically a larger danger to themselves or their passengers (who are also generally older), and they can be more susceptible to serious injuries in the event of a wreck.

Behind the Stats and the Risks Inherent to “Old People Driving”

I dislike that term — “old people.” I’d like to believe that 50 is the new 40, and so on. Healthy people can live a long time and function at a very high level. The risks, however, are the same. Some people simply have fewer of them. Now consider this:

According to a AAA study, seniors are outliving their ability to drive safely by an average of seven to 10 years. Essentially, our ability to drive safely does not coincide with our ability to live longer. So what are the signs you are too old to drive?

Physical Limitations for Elderly Drivers

Physical abilities naturally decline as we age. Our reaction time slows. Coordination suffers. The most dangerous physical change, however, may be what happens to our vision.

According to a study by the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB), when compared to Americans 18 to 44 years of age, Americans 65 to 74 years of age were more than twice as likely to report vision loss, and those 75 years old and over were nearly three times as likely. Does your senior loved one wear corrective lenses? When was the last time that prescription was updated?

Here’s why I asked: In a nationally representative study of serious U.S. crashes, the most frequent error made by drivers ages 70 and older was “inadequate surveillance,” much of which depends on visual ability. Causes included “looking but not seeing” and “failing to look.” Drivers ages 70 and older were statistically more likely than drivers ages 35 to 54 to make inadequate surveillance errors or to misjudge the length of a gap between vehicles or another vehicle’s speed.

Vision, or lack thereof, plays a prominent role in these accidents.

Mental Limitations for Elderly Drivers

Part of our ability to react to a situation is our ability to quickly diagnose what’s happening. Cognitive decline is a fact of life. Some people experience a sharper decline than others, and at different ages. In the “inadequate surveillance” example above, a cognitive issue can easily contribute. The more risk factors there are, the higher the overall risk.

Being able to see what’s happening is the first step, but analyzing the situation is next. What happens when there’s a lot going on and your ability to pay attention to your surroundings is impaired? For example, drivers 80 and older were twice as likely as drivers aged 16 to 59 to be involved in fatal multi-vehicle crashes at intersections. The most common error most seniors make that causes crashes? Failure to yield the right-of-way — an error for which seniors are cited more often than teens.

According to research, about 20% to 25% of Americans over age 65 have some level of mild cognitive impairment — that is, problems with memory, decision-making, or thinking skills.

Medical Limitations for Elderly Drivers

Above and beyond the physical and mental aspects of driving that senior drivers must account for, there are the medical conditions and everything that goes with them. This is more than reduced reaction time or slowed mental processing: We’re talking about diagnosed medical conditions.

Here are just a few that can affect an older driver:

-

- Arthritis: Half of Americans over age 65 suffer from some form of arthritis. It’s more than just pain for many, and the inability to move or manipulate can seriously reduce driving safety.

-

- Cataracts: These affect more than 90% of those aged 65 or over, and cause at least some vision loss in half of those over age 75. Anything that affects eyesight poses a serious risk. This is over and above the natural macular degeneration that affects our vision as we age.

-

- Diabetes: More than 26% of Americans over age 65 have some form of diabetes, which can contribute to vision problems and cause nerve damage, among many other risks. There are also physical effects of blood sugar levels to consider.

-

- Dementia or Alzheimer’s Disease: More than 11% of those age 65 and older have Alzheimer’s or dementia, which are perhaps the most limiting of cognitive conditions. It’s important to monitor cognitive health, as this kind of condition can cause varying rates and degrees of deterioration.

Medication Use and Impaired Driving in Seniors

Generally speaking, older drivers are more cautious, and many self-limit their driving very responsibly. There are plenty of examples, however, of seniors under the influence of medications causing accidents. People aged 65 and older account for 12% of the population, but 34% of prescription drug use.

According to information from a AAA study, about half of older drivers surveyed were taking seven or more medications. A quarter said they were taking 11 or more. Nearly 20% were taking medications that the American Geriatric Society labeled as “potentially inappropriate medications” shown to cause impairments such as blurry vision, reduced coordination, confusion, or fatigue. These medications can raise the risk of a wreck by up to 30%.

If your older loved one is taking medications as many older Americans do, talk to them and their physicians about the risks those medications pose while driving, and inquire about how drug interaction may affect a senior’s ability to drive safely.

What Are Some Warning Signs a Senior Should Stop Driving?

Direct observation would tell you a lot, but you’d need to be riding along with them. Any of the risks we’ve already discussed could be grounds to take the keys, but it’s not that simple. Just because someone is at risk doesn’t means they’re a risk.

Here are a few things you might see that would indicate your older loved one may need to hand over the keys:

-

- Stopping at a green light, or when there is no stop sign

-

- Running through red lights or stop signs

-

- Being confused by or misinterpreting traffic signals

-

- Getting lost on familiar roads

-

- Hitting other cars or fixed objects when parking, and parking poorly

-

- Failing to yield or react to other drivers or driving conditions properly

-

- Confusing destinations, such as setting out to go somewhere and ending up somewhere else

-

- Hearing about dangerous driving from friends or neighbors who have observed them

-

- Receiving warnings or citations from law enforcement for poor driving

Taking Away the Car Keys: Suggestions for Caregivers and Family Members

Caregivers and family members who want to take away the car keys should gather the facts and come up with a plan, seek alternatives to driving that still support an independent lifestyle, and be prepared to follow through.

Before you take action, however, understand that this does not have to be an all or nothing approach. Your senior may not need to stop driving cold turkey. It will be easier to phase out driving over time than to just stop. Most seniors are already limiting their driving. You simply need to continue that behavior.

Keep in mind that losing the ability to drive is a huge fear for many seniors. It is a tangible loss of independence and can come with a bewildering number of different emotions and questions. Am I becoming a burden? Am I really a danger on the road? How will I go places? Am I going to be stuck at home?

In other words, they may fear both the loss of driving and making a mistake by continuing to drive. Every situation and senior is different. Approach this all with compassion by taking three key steps: gather facts, seek alternatives, and be prepared.

Gather Facts

Head as many objections as possible off at the pass before you ever sit down to talk. Start by gathering whatever you can that may support a change in your senior loved one’s driving habits. Have they displayed any of the warning signs? Has their health declined noticeably recently in a way that would affect them on the road? You’re not looking for a reason to take their keys — you’re looking for a reason they should give those keys to you.

Often, when presented with evidence that they may be a danger on the road, seniors voluntarily hand over the keys. If you’re not prepared or in position to take the keys and they refuse to give them up, suggest a neutral third party analysis.

For example, did you know that there are driving rehabilitation specialists available that will check your driving skills? Occupational therapists can do the same. Who knows, you may get an all clear. Plus, some car insurance companies may lower your bill if you take and pass a driver improvement course. Here are two resources to find driver courses near you: Senior Driver Safety & Mobility from AAA, and Driving Assessment resources from AARP. You can also check with the car insurance company.

Seek Alternatives

Rightfully, many seniors worry that once they stop driving, they’re homebound. But communities across the nation are offering more of a variety of ways to get around without having to drive.

Here are just a few ideas:

-

- Look into free or inexpensive bus or taxi services for seniors.

-

- Arrange carpool services for doctor’s visits, grocery shopping, the mall, hair appointments.

-

- Ask religious and community service groups, which may have volunteers on call who offer transportation to seniors.

-

- Sign up for car or driver services, which may be affordable for seniors no longer paying for car insurance, maintenance, gas and other auto incidentals.

-

- Offer to pay friends or family members to drive — it could be the beginning of more meaningful relationships.

You can also find transportation services in your area by calling 1-800-677-1116, or visit eldercare.acl.gov to find your nearest Area Agency on Aging.

Be Prepared

You already have a wealth of information you can share with your senior loved one, but this could be a very emotional conversation. They may become defensive, and it’s difficult to come up with a rational solution when someone is feeling attacked.

For that reason, when you choose to have the conversation, determine how you will initiate it and the words you will use ahead of time. Don’t “ambush” them, and you may not even want to initiate directly after a driving error (when they’re likely already feeling ashamed or defensive). Consider doing it after a meal, during a commercial break, or whenever they’re in the mood to chat.

As we stated upfront, this need not be all-or-nothing. Have a plan in mind that includes perhaps keeping the senior behind the wheel but in a limited capacity, like driving only during the day and only to familiar places. Engage a local senior center or council on aging. These facilities are typically equipped to help with rides and to help caregivers deal with the question of whether seniors should stop driving.

Also important is for family members, friends, and caregivers to remember that a senior’s ceasing to drive could result in additional responsibilities for them, like providing rides for the senior and spending more time with them. Help set up these alternatives for them.

What if My Older Loved One Refuses to Stop Driving (Even Though They Should)?

This is the most difficult situation of all. They may not volunteer for a test, and their physicians may be hesitant to order them to stop driving (and even then, would they?). You may or may not feel comfortable taking the keys away, and if you do so, know that there could be consequences outside of family drama.

For instance, if your senior is the owner of their vehicle, pays insurance, and so on, then taking their keys could come with some legal headaches (which we’re trying to avoid, after all). Without proper documentation of conditions that should keep them off the road, you could find yourself in a legal bind. Here are some ways you can go about getting the keys (hopefully without the legal drama).

Consult Their Physician or Eye Doctor

Approach your elder’s physician, optometrist, or ophthalmologist and bring any evidence of dangerous driving with you. This assumes your senior likes and respects the opinion of their medical providers. Sometimes, a doctor can have the “driving” conversation and do so from a position of authority — something you may not have in your senior’s eyes.

A physician may be able to provide you with a medical status report or visual exam result that you can take to the DMV, as I will discuss further below.

Engage an Elder Law Attorney

If your loved one has an estate plan, or uses an attorney, you may want to approach them about the situation. If the medical professionals cannot help, or if your loved one refuses to consider those opinions, an elder law attorney may be the final straw to changing their minds. Make an appointment.

The attorney could ask a number of questions about what might happen to their estate or finances in the event of an accident. Most seniors tend to be conservative and risk averse when it comes to finances. Perhaps your loved one is frugal and concerned with what they’re leaving their children and grandchildren, especially on a fixed income. These questions could open their eyes and ease their grip on the keys.

Head to the DMV

When is an elderly driver’s license revoked? Does the DMV test for seniors? At what age do they take your driver’s license away? It would be easy if the DMV simply told your aging loved one they could no longer drive. The problem is that the rules are different for different states.

Note that none of the states automatically revoke a driver’s license based on age alone. In some states, when you turn a certain age, the required time between renewals is shortened, and a visual test may be required.

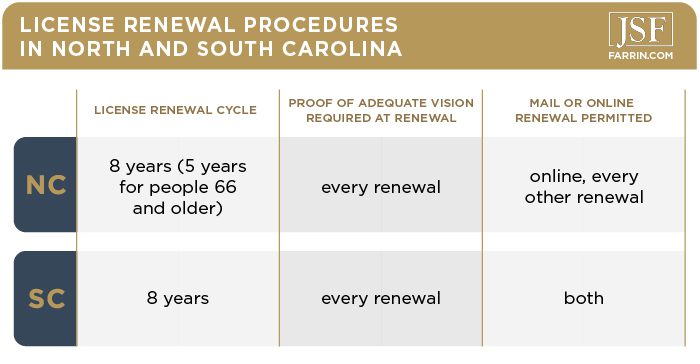

You can see your state’s license renewal requirements (and note that the pandemic may have tweaked these rules slightly). Here are the requirements for North and South Carolina as of September 2021, courtesy of the IIHS:

Offer Tips for Safer Driving

Offer your senior loved one some tips on staying safe on the road. There are lots of lists you can find with a cursory online search, but here are some of our favorites:

-

- Silence your cell phone! Nobody should be interacting with their phone while driving, especially seniors. If you must use the phone, wait until you reach your destination, or park somewhere safe to use it.

-

- Don’t eat while driving. Seniors are already dealing with a natural decline in coordination. Adding a meal behind the wheel is a recipe for disaster.

-

- Never drive impaired. It’s easy to say you shouldn’t drink and drive, and most seniors wouldn’t. However, it’s important to remember that many medications can impair your ability to drive. Consult with your doctor and make sure you’re 100% focused behind the wheel.

-

- Watch the road and your mirrors. This may seem basic, but as visual ability naturally worsens over time, it’s even more important to stay disciplined when driving. Know what’s going on around you and if something doesn’t feel right, pull over for a few minutes.

-

- Avoid night driving and bad weather. Anything that reduces visibility is a hint not to drive. Driving in bad weather is a double whammy – it reduces visibility while also making the road more dangerous.

-

- Choose safer routes and drive times. If you can avoid busy intersections, hectic on-ramps, or crowded roads, do it! Take the back road or maybe even a slightly longer route to avoid those hazards. Also, try to drive when there are fewer cars on the road. Avoid rush hour, for example.

-

- Don’t drive if you’re feeling tired or stressed. They may seem quite different but they can have the same effect – reducing the mental horsepower you can dedicate to the act of driving.

Can’t I Just Report My Elderly Driver to the Authorities?

You can file a report with the DMV about an unsafe driver, but the requirements for those reports vary. For example, in North Carolina, you cannot file that report (or complaint) anonymously, and advanced age cannot be the sole reason for a medical examination according to the North Carolina Department of Motor Vehicles.

As mentioned earlier, documentation from a medical professional could come in handy here. Check the local DMV rules where you live, as they will all have a process for reporting a dangerous driver or requesting a medical evaluation.

Also, be aware that this may be a genie that won’t go back into the lamp: once your loved one is determined to be incapable of driving by the state, it would be hard to regain that privilege. For this reason, you may not want to take this approach if the condition causing their erratic or unsafe driving is or may be temporary.

Taking the Keys Away From Aging Parents and Loved Ones Is Tough, But It May Save Lives

I hope that this has helped you answer some questions and perhaps formulate a plan that will work for your elderly loved ones. No one wants to be the “bad guy,” and if you approach the conversation properly, no one has to be. These are parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles. People we love. We don’t want to see them unhappy. We want to see them safe, not calling us because they’ve been hurt out on the road.

At the same time, the roads can be a dangerous place whether your senior loved one is good to drive or not. As car accident attorneys, we have seen more than our fair share of avoidable tragedies. We don’t want our aging loved ones to become statistics or to hurt anyone else. I think that’s something we can all agree on.

You May Also Be Interested In

Answers to the Most Frequent and Urgent Car Accident Injury Questions

Car Accident Statistics in North Carolina

Important Facts About North Carolina Car Accident Injury Claims