Even though fewer drivers are on the roads during the COVID-19 pandemic, law enforcement agencies in some areas are seeing an alarming trend. Minnesota and Louisiana have recorded more traffic deaths during the coronavirus outbreak than for the same period in past years despite the reduced amount of traffic.

What’s driving the increase in traffic fatalities, even though the roads are clearer? In a word: speed.

Speeding: The Epidemic Within a Pandemic

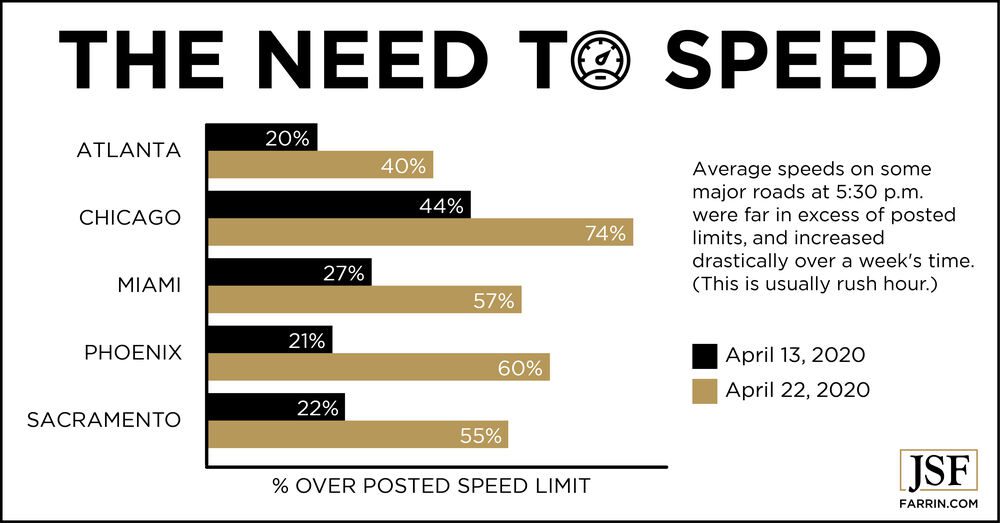

When drivers see clear sailing, they seem to be putting the pedal down all across the country. Reports of increased speeding, higher average speed on roads, and increased rate of fatalities in accidents are not hard to come by.

-

- In Pasco, Washington, police are noting speeders going 15 – 30 mph over the limit. The department even posted a warning on its social media page against street racing.

-

- The Colorado State Patrol issued more citations for 20+ mph over and 40+ mph over the speed limit through March 2020 than it did in March 2019, despite reduced traffic volume.

-

- For the one-month period starting on March 19 when California’s stay-at-home order was put in place, the California Highway Patrol reports it has issued 87% more citations for drivers exceeding 100mph than it did for the same period a year ago -2,493 statewide versus 1,335 a year ago – despite a 35% reduction in traffic volume (or perhaps because of it).

-

- Police in Fairfax County, Virginia have cited drivers going 125mph and faster, and report that speed-related traffic fatalities have risen 47% since March 13, 2020.

-

- In Connecticut, the number of drivers traveling 80 mph or greater has doubled overall – and in areas increased as much as eightfold. Meanwhile overall traffic volume has declined by half over the previous two-year average on certain major roads. The number of drivers traveling at 80 mph or more on those same roads has increased 94% over the previous two year average.

-

- In response to a 30% increase in average speed for its drivers, Los Angeles modified its traffic signal programming to slow them down.

-

- In Washington, D.C., a longtime traffic reporter saw two separate crashes requiring Medevac on the same stretch of I-270 within six hours of each other, with one car vaulting the median and landing in a tree. He said it was the first time in his decade of reporting that two such serious accidents happened on the same day, much less the same stretch of road.

-

- In New York, automated speed cameras issued 24,765 speeding tickets on March 27, almost twice as many as the daily average a month before despite there being fewer cars on the road.

There are similar reports from nearly every tier of law enforcement nationwide. People are taking advantage of reduced congestion to increase their speed, sometimes to a ridiculous extent. A driver in Michigan was cited for doing 180 mph – a record for the state.

The Higher the Speed, the Bigger the Hurt

When most people speed their biggest worry, if there is one, is getting a speeding ticket. The fine and the possible effect on their insurance rates are the only things they seem concerned about, and those can be significant financial penalties. However, speed has another effect. It increases the likelihood of serious injuries or fatalities. Consider:

-

- According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an increase in average speed of just 1 kph – not even a single mile per hour – typically results in a 3% greater likelihood of a crash involving injury, and a 4-5% increase in the chance of a fatality.

-

- The Institute for Road Safety Research has calculated that, if the average speed on a road decreased from 120 kph (74.5 mph) to 119 kph (73.9 mph), car accident fatalities could be reduced by 3.8% and serious road injuries could fall by 2.9%.

-

- A University of Adelaide (Australia) study showed that the risk of an accident with serious injury doubled with every 5 kph a car was traveling above 60 kph. That’s every 3 mph over 37 mph for us here in the United States.

Where the Laws of Traffic and Physics Collide

If I told you that you were twice as likely to lose a limb for every 3 mph over 37 mph you traveled, would you slow down? I understand that’s a grisly and drastic example. Posted speed limits are there because the government considers those speeds reasonably safe to maintain, so let’s substitute the posted speed limit for 37 mph. So, if your risk of losing an arm or a leg doubled for every 3mph you were traveling over the speed limit, would you still be speeding?

Obviously not every car wreck results in a serious injury such as the loss of a limb, but the potential is there and the risk increases exponentially the faster you travel. Why? That’s simple: physics.

I won’t post a bunch of formulas here, but understand that you and your car, traveling at a certain speed, carry with you a certain amount of kinetic energy – the energy of motion. If your car were to suddenly stop traveling at that rate of speed, in an accident for example, that energy doesn’t just disappear. You can read up on the Law of Conservation of Energy here if you like. The point is, that kinetic energy doesn’t disappear; it has to be converted into some other form of energy.

Kinetic energy in a car accident is exerted/dissipated/dispersed in two ways. Because every action has an equal and opposite reaction, some of that kinetic injury doesn’t convert, it just goes the opposite direction. The car may be stopping in a hurry but you’re not part of the car so you keep traveling until you hit something — hopefully a seat belt or an airbag. Those safety devices are designed to take on the “equal and opposite reaction” that would force you to absorb all of that kinetic energy from the crash.

The other way kinetic energy is dispersed is into potential energy. Energy can be stored in matter. Think of a spring. If you compress it, you’re turning your force on it into potential energy that’s released when it rebounds. This is basically what crumple zones in cars are. They’re kinetic energy sinks that transform the force of a crash into potential energy. They work extraordinarily well but they have a limit, and once that limit is reached you and other people become those crumple zones. Our bodies aren’t designed to do that, and that’s why serious injuries or deaths occur.

Slow Down, Stay Safe, and if Someone Causes an Accident and You’re Injured, Call Us

The temptation to floor it on the newly-clear roads is a trap. Not just a speed trap, it could be a death trap. Stick with the posted limits. Put away your distractions, and concentrate on getting where you’re going safely.

We can’t protect you on the road, but if some reckless soul does cause a wreck and you or someone you love is injured, contact an experienced personal injury attorney to protect your rights. Contact the Law Offices of James Scott Farrin online or by calling 1-866-900-7078 for a free case evaluation. And drive safely!

You May Also Be Interested In

Answers to the Most Frequent and Urgent Car Accident Injury Questions

Did Government COVID Response Result in More Traffic Deaths?

N.C. Police Target Aggressive Drivers in Ghost Cruisers

House Bill 158: Untested Teen Drivers Hit the Roads, and Parents May Be Liable for Their Accidents